|

The book is devoted to the ideas of the Muscovite State that took shape at the turn of the 15th century. Ruled by one of the most eminent monarchs of the Grand Duchy of Muskovy, or Russia itself, Ivan III of the house of Rurik (1462 - 1505) the country managed to shake off the tributariness to the Great Horde and began to unite successfully, predominantly through conquests, other Russian states. This became a natural reason for anxiety for the closest neighbours: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland, whose territory included the lands that Ivan III considered his heirloom.

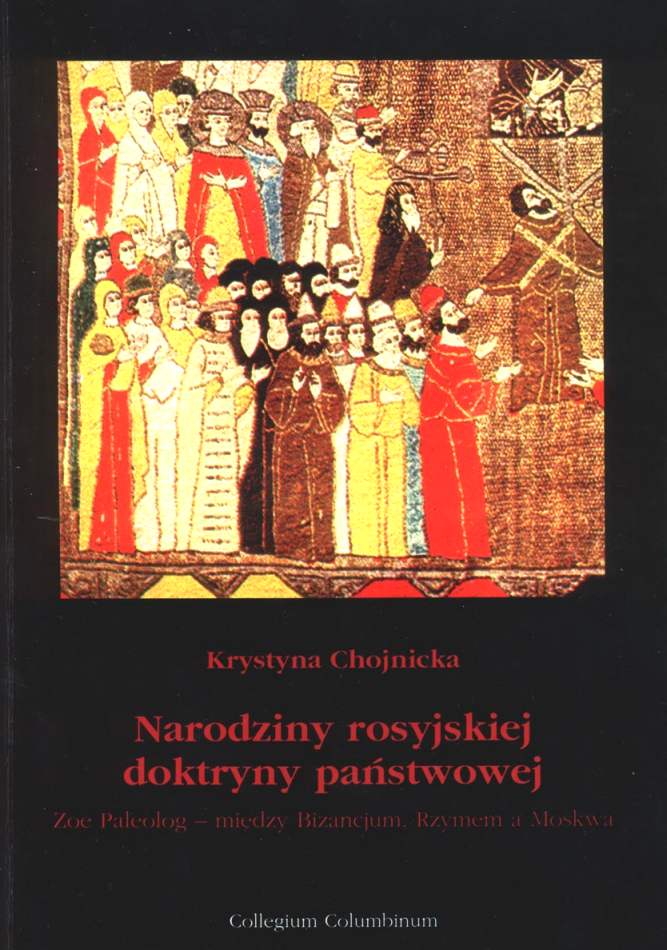

The days of growing territorial expansion, increasing international importance, and military success of Muscovy were accompanied by flourishing literature. This resulted in the number of chronicles and political writings soaring, under the rule of Ivan's successors: his son and grandson, Vasilii III and Ivan IV 'The Terrible'. Historians fairly commonly interpret them as illustrations of the idea of Muscovy being a successor to Byzantium after the Turks had conquered Constantinople in 1453. This idea was included by a monk Philoteus in his scheme presenting Muscovy as the Third Rome. In the opinion of many, this scheme had been supported by Ivan's marriage, in 1472, to a niece of the two last Byzantine emperors, Zoë. She, as Grand Duchess Sophia, reined on the Muscovite throne for 31 years and was concluded, in historiographic tradition started by the monumental work of Nicolai Karamzin, to be the main animator of contemporary transformations.

However, in the light of detailed research, the role of Zoë Paleolog, though authenticated through numerous historical works, seems to be neither so significant, nor so evidently dedicated to the Byzantisation of Muscovy. Thus, considering the influence exerted by Zoë exaggerated, the whole theory of Muscovy being the Third Rome requires verification. At that time, the concept was politically unfavourable for a number of reasons, one of them being the ruler's determination to maintain civil contacts with the Sultan. The same rulers, on the other hand, would issue considerable demands towards Lithuania and Poland. Hence the author, having presented the history of the lives of Zoë Paleolog and her daughter, the queen of Poland, Helen, as well as the dispute concerning the succession after the death of Ivan III, and all the relations that Muscovy had with Empire and Papacy, arrives at the formulation of the fundamental trends in Muscovite foreign policy. It serves as the background of a reconstruction of the arising doctrine of the Russian State. This doctrine was thoroughly secular, to such extend, as it was possible in those days, pragmatic, and decidedly avoiding any slogans referring to the Byzantine succession. Moreover, it made a reference to the legend that derived the Rurik dynasty from emperor Octavian Augustus, argued the superiority of the Muscovite Church over the Greek, and presented Byzantium as a state that had always sought for peace and alliance with the mighty Russia. These legends, combined into an increasingly convergent and logical official doctrine, prepared the premises for the birth of the Tsardom, whose founder, Ivan III, would personally frequently shape the doctrine and defend it from external criticism.

|

|