|

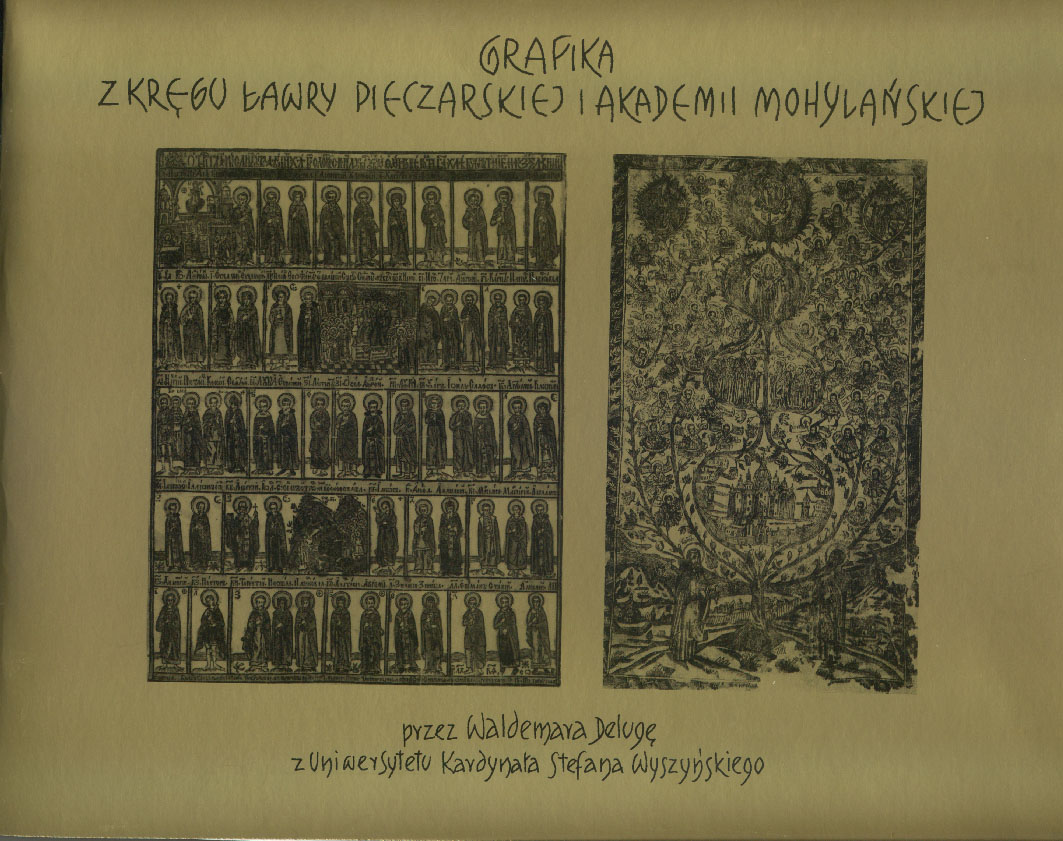

Orthodox prints associated with the Kyevo-Pecherska Lavra (Monastery of the Caves) monastery and Mohyla Collegium are among the most interesting artistic phenomena in the contemporary art of the Orthodox Church. The book focuses on a variety of artistic endeavours and enterprises that were of fundamental significance for the development of 17th-century Orthodox printmaking within the former Republic of Poland and Russia. These works are primarily old prints and leaflets. Thought but a few of the latter have managed to continue to our days, and even an extensive search did not return an imposing collection, they provide typical material to illustrate some phenomena of that period.

The first chapter presents the goal of the work, state and progress of research, proposed time frames, their justification, and the method. The second chapter contains a discussion of the Kiev artistic and literary milieu, giving details of the system of operation of the Kyevo-Pecherska Lavra monastery, printing house, and the Mohyla Collegium against contemporary events. A considerable share of the chapter is devoted to the presentation of artist printmakers operating in Kiev, with attention paid to their origin and works executed elsewhere in the former Republic of Poland. Prints used to illustrate liturgical and hagiographic publications are presented in the third chapter. Printed liturgical books are among the most rare fully preserved prints, while the preserved fragments of individual editions and their variations have been preserved in single copies. Liturgical and hagiographic prints are related to their usage for liturgy and prayer. In the 17th century, the printing house of the Kyevo-Pecherska Lavra monastery was a leading press both by volumes of impressions and numbers of works issued. Of interest, the number of works included also large-format publication whose setting required large quantities of paper ordered from many Polish and foreign paper mills.

Argumentative and publicity pamphlets, which accounted for a major share of the Kiev prints, were illustrated in an interesting manner, using the principles of emblematism and iconographic systems drawn from the Latin culture, yet adjusted to the requirements of the Orthodoxy and contents of the books. These were mostly works printed to the order of the Metropolitan of Kiev, disputing with Catholicism, and prepared to combat the Uniate Church.

The development of printmaking techniques helped to increase popularity of unknown forms of illustrating emblematic publications. Literature in the Latin and Polish languages written in Kiev Orthodox centre belongs both to Polish and Ukrainian heritage. Most of these works were published for special occasions: nominations of new metropolitan bishops, weddings and funerals, visits of notable guests, argumentative and propaganda works, as well as hagiographies prepared by students and professors of the College. The author of the book discusses the emblematic illustrations of the epithalamia, elogies, and other special occasion publications.

The fourth chapter presents devotional woodprints used in minor publications whose mass production and sales ensured serious economic benefits for the Kyevo-Pecherska Lavra Monastery. Most of printed matter of this type was hung on the walls of temples and in households, some were attached to the insides of manuscript and print covers. Many of these works catered for the needs of the metropolitans of Kiev; their number chiefly included calendars, antyminsy, diplomas for Orthodox brotherhoods, and philosophical treatises prepared by students and professors of the Mohyla Collegium. Very few works of print of this type (mostly woodprints and copper etchings by anonymous printmakers) have been preserved to this day. Examples of detached prints are not too numerous and, though these were historically widespread, only very few works of the art of print have remained: most of them in the form of book inserts and attachments or the so-called spoilage. Many of these are folk woodcuts, which enjoyed tremendous popularity among visitors to monasteries.

Discussed in the fifth chapter are sources and inspirations for Kiev works of print. The standards developed in the 17th century influenced the whole territory Republic, reached Russia and the Balkans. Kiev became the agent for carrying new ideas to territories lying further away from major printmaking centres.

In the considerations concerning the significance and value-judgements of prints connected to the Kyevo-Pecherska Lavra monastery contained in the last chapter, the author attempts at a classification of prints produced in the Orthodox world. This type of prints, with abundant examples preserved, belongs to the group of works made to the order of the Orthodox Church. It allows complementation of the knowledge on changes in the iconography of the 17th century as well as on terrible losses due to wars and fire, assisting in the reconstruction of the complete image of artistic life in the border lands of the Republic. The illustrations show more than just iconographic elements: there are scenes depicting the customs as well as cityscapes that allow reconstruction of the unpreserved elements of Kiev built heritage. The prints are a perfect basis for tracing the changes in the artistic thought, and pinpointing the sources of inspiration and flow of iconographic themes. |

|